Introducing Virtual Private Network (VPN)

A Virtual Private Network (VPN) is software that masks your IP address and makes it look like you’re coming from somewhere else, by routing your Internet activity through a server. It's a bit like a tunnel between your device and a website, with your data travelling through that tunnel.

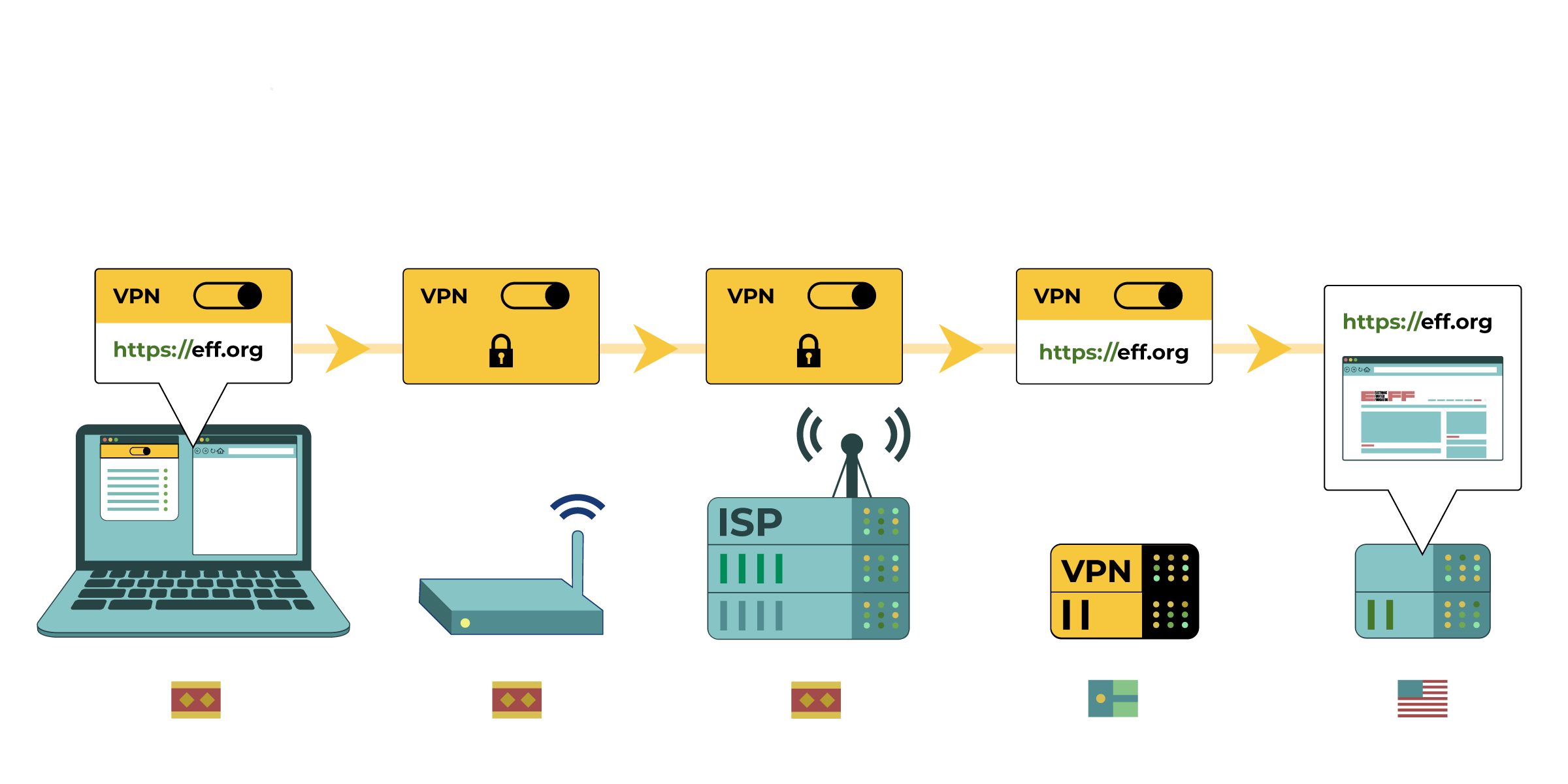

The graphic above is a fantastic illustration of how a VPN works. It was designed by the EFF, which described VPNs as follows:

A VPN routes all your web traffic through an "encrypted tunnel" between your devices and the VPN server. Then, the traffic leaves the VPN to its ultimate destination, masking your original IP address. From a website's point of view, it appears your location is wherever the VPN server is. A VPN also hides your web browsing from your ISP and the local network owner (like a coffee shop or hotel).

How VPN works

As the graphic shows, when you use a VPN:

- The VPN is installed on your computer or mobile device, and figures out which pages you want to visit. It forms a tunnel to this page

- The internet router at your home, library, cafe, or other places where you access your internet does not know what you are browsing. It only knows you are using a VPN. It can only see the "outside" of the tunnel, not what's in it

- Telecoms and internet service providers similarly only see you use a VPN, not what you use it for.

- Finally, the VPN contacts the website you visit on your behalf. The website only knows that a VPN is asking it for specific information and only sees its IP address. It does not know what the original IP address or location is of the person making the request

VPNs also prevent telecoms from knowing what you are browsing. All a telecom (or anyone else who runs your internet connection) will see is that you are connected to a VPN.

In some countries, VPNs are illegal and using one or having one installed on a device can put the person at risk. In those countries, governments may have issued government approved VPNs that can be used. These are not secure and will be collecting personal data on the users, including their browsing history. If you are leading a training on VPNs, or even just researching them for yourself, it's important to read about the legality of VPNs and the consequences of ignoring any laws on them.

There are a wide range of VPNs available. Unfortunately, many of them track their users and some even share information with governments or advertisers. We recommend checking out this excellent article by Wirecutter or this article from Center for Democracy & Technology on how to pick the VPN which works best for you. When choosing a VPN it is important to consider the following:

- Choose a VPN that does not log the user’s browsing history. This information could be shared with governments. Do note, however, that some VPNs have lied about their capabilities or privacy promises.

- Find out who owns the VPN company, where is it based, and where are its servers based. This information can be found on the website of the VPN you want to use. For people facing threats from a government, it is best to choose a VPN that is not located in their country or in any country that has close relations with their government. This is because the VPN provider could share data with their government.

- Free VPNs can often contain malware, keep extensive logs, or resell your browsing data or bandwidth. Speak with others on the ground or with digital rights organizations such as Access Now to see what VPNs they are using.

- Does the VPN work in the country you want to use it in or has it already been blocked by the government? Ensure you have a number of VPN options available should one stop working.

When you visit a website, the person running the website will also typically know your IP address. Based on this, they could figure out your approximate location (such as region or city), whether you are a repeat visitor, and more. If the police requests it, the owner of the website might even need to share the IP addresses of visitors with them. As such, using a VPN is a good idea if you do not want the website owner to know that you are visiting their site.

VPNs do not protect you against all tracking. You still need to protect yourself against cookies, so combining VPNs with other mitigations such as private/ incognito mode is ideal.

Circumventing Internet Censorship

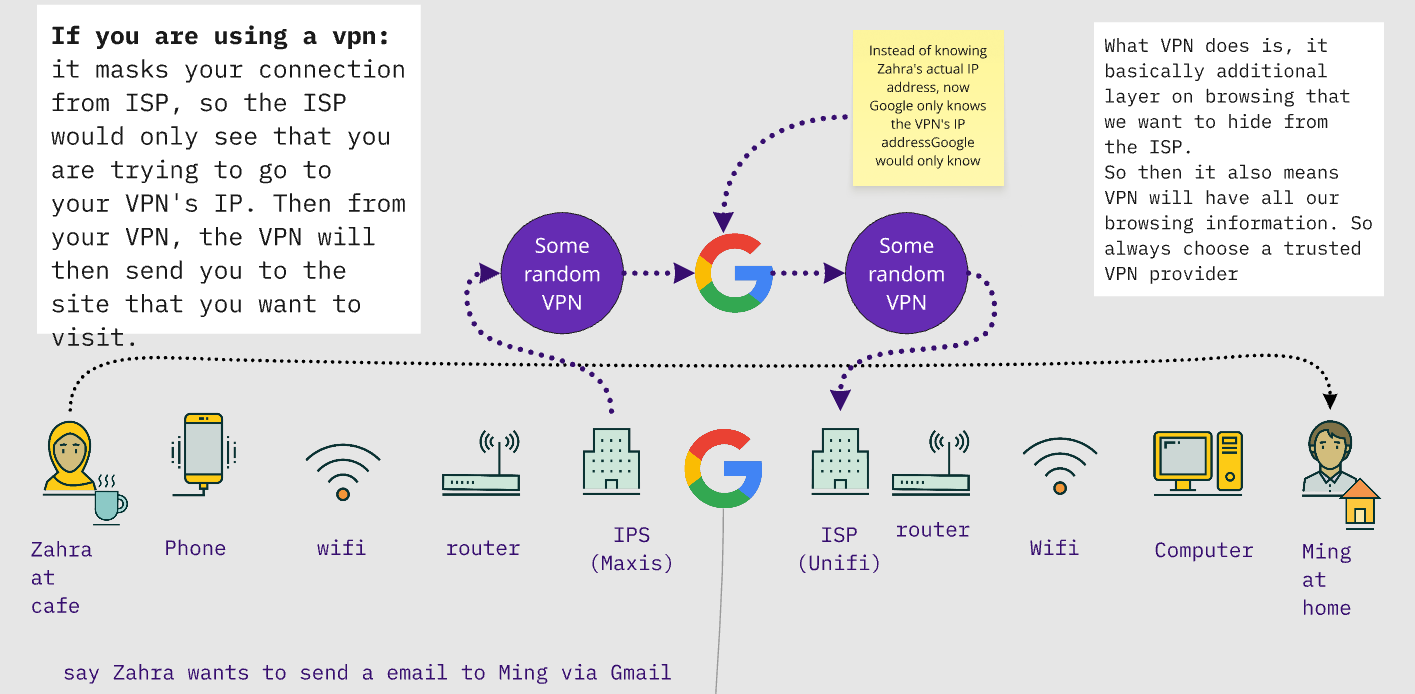

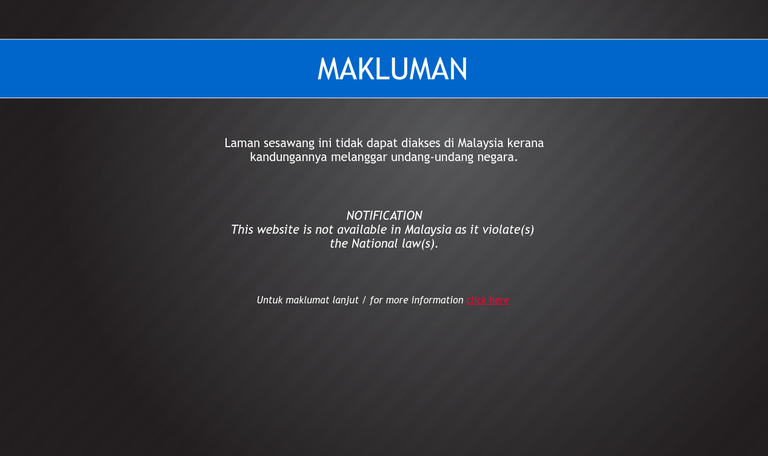

In Malaysia, pornography, gambling, sometimes human rights, news sites, and LGBT websites are blocked. VPN is a common way to access these blocked sites. The above graphic illustrates the website blocking method: DNS Tampering. Essentially, MCMC tells Unifi whenever they see someone accessing a blocked website like Planetromeo.com they will direct to the the page that informs users the website is blocked (like the Makluman page above). Read here for further explanation.

In general, people can browse blocked website via:

- Public DNS

- VPN

- Tor Browser (we discussed this during the sync session)

Using Public DNS

Public Domain Name System (DNS) is a common way people use to browse blocked website, namely the Google DNS (8.8.8.8 and 8.8.4.4) or Cloudflare DNS (1.1.1.1). We are not covering DNS in details, as it does not make our browsing any safer. Early this year, the Malaysian Communications and Multimedia Commission (MCMC) implemented a DNS forced redirection to local DNS, the plan has been suspended since.

End note

VPN is a very common tool people use, however it is a common misconception that VPN provides anonymity. A VPN essentially takes over the role of an ISP. In the context of Malaysia, our ISP is less trustworthy since they work with the police, government to block website and collect data. Choosing the wrong VPN however may cause more harm, VPN is now a huge industry globally and bad VPNs collect a lot of data and sell those data.

Further resources:

- This explainer video about VPN by Tom Scott

- Explainer video on DNS

**This material is gathered from SaferJourno, CDT, and Level Up. Several sections, notably the VPN graphic and description, were adapter from training materials designed by the EFF (Electronic Frontier Foundation)